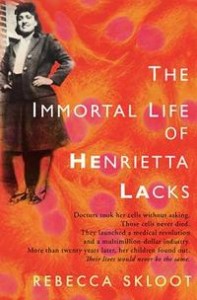

You go for a routine skin cancer scan at your dermatologist’s. They remove a small piece of skin that looks suspicious and they send it to the lab for testing. You’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer and the prostate is removed and tested. You’ve had a hysterectomy and all the organs are sent out to be tested. Then what? What happens to those pieces of skin or organs? Thrown into the medical waste bin? Sometimes yes, sometimes NO. In 1999 the RAND Corporation estimated that American labs alone held more than 307 million tissue samples from 178 million people. Didn’t know that, did you? And neither did the family of Henrietta Lacks. Read more…

Henrietta was born into a poor sharecropping family in 1920. When she married, she moved to Maryland with her husband and 5 children. Her husband was not faithful by any means and repeatedly infected her with sexually transmitted diseases particularly HPV’s (human papillomavirus).

And in 1951, at the age of 31, she began to realize that she had a “knot” inside of her and went to Johns Hopkins Hospital to find out what was wrong. She had cervical cancer. While they were packing her insides with radium, the doctors, unbeknownst to Henrietta or her family, took two dime sized slices from her cervix, one from the cancerous side and the other from the healthy side. And history was made. (She died 6 months later.) You see, up until this point, human cells could not be grown outside of the body. And human cells were needed for experimentation which meant, at the time, they needed humans for the experiments. But Henrietta’s cells went ballistic in the petri dishes (because of an enzyme that keeps them from aging). From that one little piece of dime sized tissue has come an estimated 50 million metric tons of HeLa (Henrietta Lacks) cells. They have been used in research to develop the first polio vaccines, test chemo drugs like Taxol, find treatments for AIDS and map gene onto human chromosomes. They’ve even been into space and blown up in a nuclear weapon.

Rebecca Skloot first heard about HeLa cells in college and while in graduate school, soon began to see a story involving science and society. She found evidence that the cancerous cells had been injected into prisoners and that Henrietta’s cells had been cultured, disseminated and sold without her or her family’s knowledge or consent. Biotechnology companies made millions selling HeLa cells with her children never seeing a dime. Skloot veers back and forth between the science of the cells and the crushing poverty and illiteracy of Henrietta’s descendants. The family first gets a glimpse of something when a cousin calls and tells them, “Part of your mother, it’s alive!” They can’t understand this. As cousin Cootie put it, “Nobody round here never understood how she dead and that thing still livin. That’s where the mystery’s at.” Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah, is the main focus in the story about the family because she never really knew her mother and was the most disturbed by her lack of understanding of science. She says, once she gets to see the cells of her mother, “Oh, God, I can’t believe that is my mother!” She had a fear that experimental fusion of HeLa cells would produce a “human monster that is half her mother, half tobacco.” Henrietta’s descendants never got a penny from HeLa cells but Skloot has put together a trust fund with proceeds from the book for their educations.

But here is the point of the whole book. Yes patients’ names and records are now private but doctors can still remove, profit from, and even patent a patient’s tissues or DNA without permission. In a 1980’s case a man found out that a doctor who had removed his cancerous spleen had patented some of his cells to create a cell line then valued at more than $3 billion. The man sued and lost. It is still not necessary to obtain consent to store cells and tissues taken in procedures and then used for research. My book club thought it was fine because it was all for the greater good. What do you think?

Leave a Reply